As the colonies along the eastern seaboard of America became settled and the land all taken up, adventurous families pushed over the mountains into the wilderness and began the westward expansion that did not stop until the Pacific shores were reached and the lands between explored and settled. The family was a part of that great expansion.

Harriette Threlkeld once wrote, “Studying the family, seeing it as a whole, it has seemed to us to be typically American – of the sort that has made up the ‘backbone’ of American life. None were very wealthy, none were extremely poor. All that I have ever known or met have been good people, most of them intelligent, capable, and with a variety of skills and talents.”1Verner M. Claybourn and Harriette Pinnell Threlkeld, Supplement to the Claybourn Family (Threlkeld, 1979).

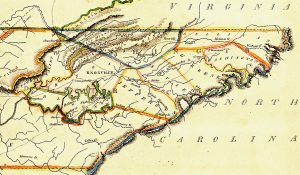

Eastern Tennessee was explored and settled by the descendants of colonists east of the Blue Ridge Mountains. They were a hardy and daring breed, the only kind who could fight Native Americans and wrest a living from the wilderness at the same time. Most of them came into Tennessee from Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. A tribe of Indians called the Tomahitans lived in eastern Tennessee. They were first visited by two Englishmen, James Needham and Gabriel Arthur, in 1673, and thereafter trade was established between them and Virginians and later Carolinians.2Will T. Hale, History of Dekalb County, TN (Nashville: P. Hunter, 1915; repr., McMinnville: B. Lomond Press, 1969), 254.

“The Carolina Road” was a path around the mountains to reach the “Overhill” Cherokees and was used until 1740. In that year a packman named Vaughn discovered the famous Native American trail called the “Warrior’s Path” which led one through southwestern Virginia, across the Nolichucky and French Broad Rivers, passing within a few miles of the future site of Knoxville and on into Cherokee country.

The Holston River unites with the French Broad to form the Tennessee River. It was named for Stephan Holston who in 1748 made a trip of exploration down the Tennessee, Ohio and Mississippi rivers to Natchez. The French Broad was given that name because it flowed west through the French-claimed region, although it rises near the Broad River of North Carolina, which flows into the Atlantic Ocean.

The upper part of eastern Tennessee began to be settled in 1763 after the peace following the French and Indian War, which was really a war between the French and British. Sullivan and Hawkins Counties in the northeast corner of Tennessee were settled by 1772, mostly by people from Virginia. The Watauga Association of settlers came into Tennessee from North Carolina and spread over the eastern section.

In 1783 the state of North Carolina adopted a policy of disregarding Native American title to the land and threw it open to purchasers on very easy terms, reserving for the Native Americans the southeastern part of the present state of Tennessee (south of the French Broad and Big Pigeon Rivers). The state charged ten pounds for a hundred acres, about $1,500 dollars in modern currency.

Because of this land policy, eastern Tennessee was soon swarming with men eager for land. What is now Knox County, west of the Tennessee and Holston rivers and between the Holston and French Broad rivers, was included in the area. One of the earliest cabins was built by James White. He was among a group who came into the region in 1783. Two years later there were cabins along the banks of the Holston and French Broad, but White moved farther south to the site of Knoxville, and four cabins were built with a stockade between. At this time all of present Knox County was within the bounds of Greene County, North Carolina. Most of the inhabitants living outside the Cherokee Reservation had North Carolina warrants under the land act of 1783. These titles were also recognized by the State of Franklin, organized in 1784, which was attempting to get Native American consent for their occupation of the land.

When the State of Franklin did not become a reality, the residents of (future) Knox County returned their allegiance to North Carolina, expecting to again become part of the United States. But in 1789 North Carolina ceded its western claim, and the area was orga-nized in 1790 as the Southwest Territory, much like the Northwest Territory. William Blount of North Carolina was governor.

That same year the nation’s first census was taken and Joshua, Ephraim Claybourn’s father, was living in Fayette District, Robeson County, North Carolina. But less than two decades later, the family would make its way to the area. In 1791 Blount signed the Treaty of Holston with the Cherokees which gave the settlers clear title to their land. Beside the Native American names, William Blount and George Washington, the treaty was signed by a number of witnesses, including a Claiborne Watkins of Virginia.

A year later, in 1792, Knox County was formed. Knoxville became the capital of the territory, and William Blount’s home was built there, the first frame house of the mountains.

Early Days in Knox County

The Native Americans and early settlers in Knox County raised corn, beans, peas, pumpkins, gourds, squash and May apples (mandrake). Their meat was hunted. Buffalo, deer and bear gave meat, wool, hides, leather, sinews for cord, and horns for utensils. The Native Americans had dogs and turkeys as domesticated animals. In general, game was plentiful.

In some cases the men came first alone, planted corn, and raised a crop. Then they would return to Virginia or Carolina for their families and settle the following year. The main implements were the rifle, axe, hoe, sickle and/or scythe. 1795 to 1830 – the years the family of this society made their way to eastern Tennessee – were a transition period from hunting and raising a few crops to settled fields and livestock raising. From 1830 to 1860 agricultural production increased.

The Knox County Court in 1792 ordered roads built in several directions from Knoxville, and a ferry crossed the Tennessee River. According to ads in old newspapers, in 1792, beeswax, skins, furs and flax were taken in trade by merchants. By 1795, butter, tallow, hemp and linen were being purchased.

Between 1795 and 1830 pack trails gave way to roads with coach services to the east, and west as far as Nashville, soon following. Four, six, and eight horse freight wagons hauled supplies, but the rivers were still widely used for downstream transportation.

The Battle of King’s Mountain was an important American Revolutionary War battle, and many of the men who served in it were given grants of land. An Enos Browning of Washington County, Virginia, obtained a grant of land in Tennessee. A John Clayborn, aged seventy-four in 1832, served in the Virginia line, drew a pension beginning in 1833 in Knox County, and died 4 September 1838. Being thirty years older than Ephraim, he could be his uncle. A John Cleburne, the same age as the John above, (82 in the 1840 census) drew a pension in Sumner County and lived with his son George Cleburne.

Jacob Lonas, of German extraction, came from Pennsylvania and was probably the second man to settle in the early community of Bearden, which was first called Erin, five miles west of Knoxville. Indians were still so hostile that he returned to Pennsylvania for two years, and then returned with two of his brothers and their families. He settled on a tract of land acquired from North Carolina on what is now Middlebrook Pike. His descendants, Charles Dowell and daughter Mary, still lived on the place in 1945 and possessed several old deeds, one dated 12 January 1794, in which the state of North Carolina sold 200 acres of land for 100 shillings, approximately $12.50.

The Lonas place was about two miles northeast of Cavet’s Station, and the family saw the light of the burning fort when it was attacked by Indians in 1793. There is a Jacob Lonas Library of German books, and many pieces of very old furniture remain in the home. Logs from the original Lonas cabin are now used in a corn crib. Jacob Lonas is buried in an unmarked grave in a community burying ground on what was once the Matt G. Thomas Estate on Weisgarber Road, Knoxville.

There is another cemetery of old settlers in the back of what was once Spring Place Church on Love’s Creek. Several Claibornes are buried in the Shipe family graveyard around old Bethlehem Church in the eastern part of Knox County.

In 1802 Knoxville had 200 houses nearly all built of wood. Merchants got supplies by land from Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Richmond and sent goods there. They would also send flour, cotton, and lime down the rivers to New Orleans. There were about fifteen or twenty stores, but there was no manufacturing except tanneries.

Footnotes

- 1Verner M. Claybourn and Harriette Pinnell Threlkeld, Supplement to the Claybourn Family (Threlkeld, 1979).

- 2Will T. Hale, History of Dekalb County, TN (Nashville: P. Hunter, 1915; repr., McMinnville: B. Lomond Press, 1969), 254.